Shooting the Ayatollah.

Photojournalism, the press, the foreign policy public, & the Iran Hostage Crisis.

Originally published by the University of Georgia, May, 2007.

Abstract.

This history thesis—researched and composed as part of my Masters in History program at the University of Georgia—quantifies the volume, type, and tone of images used by the mass-market newsweeklies—Newsweek, Time, and U.S.News and World Report—to depict Iran and the Iran hostage crisis in an attempt to characterize related media coverage. In four chapters, this study’s quantitative approach describes the entire lifecycle of hostage crisis media—from its creation in Tehran and Washington by news service reporters and Iranian photojournalists, its communication on the pages of the American news magazines, a statistical examination of news media consumption by various strata of American society, and a comparison of the American press and its Arab analogue. This thesis also tests a number of core assumptions about hostage crisis media coverage that dominated the contemporary press and continue to linger in the current historiography, providing a new, more accurate image of the crisis’s cultural impact.

Chapter 1: Introduction.

The Iran Hostage Crisis as a cultural product.

“Mr. President, I hope you were watching TV…”

– Former hostage, Bruce Laingen [1]

A large demonstration was already underway when, shortly after 10:00 am on Sunday, November 4, 1979, a small group of chador-clad women from the Tehran Polytechnic University marched past the motor pool gate of the U.S. Embassy. The women suddenly reversed course and surrounded the Iranian guard stationed at the gate. Three hundred more students emerged from adjoining streets and crossed Takht-e-Jamshid Avenue – a road that, before the revolution, had been named in honor of Franklin Roosevelt – to cut the locks on the embassy gate and scale the compound’s eight-foot walls. The uniformed Iranian soldiers stationed on the American compound to protect the reduced embassy staff lowered their weapons and greeted the students with kisses.

The students, a group calling themselves the Muslim Students Following the Imam’s Line, locked the gates behind them, preventing the even larger mob outside from gaining immediate access to the embassy. Wearing headbands that read Allah-u Akbar (الله أكبر) – “God is great” – and black and white bibs bearing the likeness of the Ayatollah Khomeini, the students split into groups and headed toward the four main buildings scattered across the 26-acre American compound.

Figure 1.1 — The U.S. embassy compound in Tehran. [2]

In the chancery, a two-story rectangular building faced with narrow yellow bricks set back from the street on a circular drive (figure 1.1), Colonel Chuck Scott, the U.S. Army military attaché, watched on the lobby guard post’s closed circuit TV as the mob swarmed through the gates and over the walls. He may have even seen an Iranian woman approaching the chancery carrying the misspelled sign, “Don’t be afraid. We just want to set in [sic].” Within minutes, the chancery staff retreated to the second floor security vault where Scott and Elizabeth Ann Swift, chief of the embassy’s political section, frantically called Washington and Bruce Laingen, the embassy charge d’affairs across town at the Iranian Foreign Ministry. Meanwhile, marines armed with shotguns, flak jackets, and gas masks tried using tear gas to slow the penetration of the building through weakened basement window grates.

On the other side of the compound, Robert Ode, a retired Foreign Service officer on temporary duty in Tehran, watched from a second floor window as students approached the rear of the consulate. The staff and visitors sat huddled in an upstairs hallway hoping the students would pass by the empty downstairs windows and leave the building for empty. But word came from the chancery that they had been breached – a marine crackled through the consulate guard’s walkie-talkie: “You’re on your own. Good luck.”

The consulate staff decided to evacuate the building, releasing the Iranian staff and visa applicants before the American visitors and consulate staff. When it came time for Ode to step outside he was surprised to find the street quiet – the students and demonstrators converged on the chancery, leaving the consulate unguarded. He stepped into the first weak rain of the season and, with five other staffers, started away from the embassy compound along back streets. They barely made it half a block before a large group of Iranians surrounded them. Ode and the other Americans protested, trying to push their way through the crowd, until a shot rang out over their heads and men armed with pipes, pistols, and automatic rifles surrounded them.

Back in the chancery, matters had gotten worse. Armed students captured off-duty staff in their homes and brought them to the compound. Security Chief Al Golacinski went outside to talk with the militants but was instead bound and blindfolded. When Scott tried calling the Ambassador’s residence an Iranian voice answered the phone. Looking outside, he saw students roaming the grounds outside the chancery, ropes and blindfolds clutched tight.

The students started setting fires around the chancery, trying to smoke out the Americans, and dragged Golacinski in front of a security camera, threatening to kill the security chief if the chancery staff did not surrender. While reporting these developments over the phone to Laingen, Scott received the order to surrender. Once the communications staff was secured in another interior vault, giving them more time to destroy sensitive documents, the marines opened the security doors. Student protestors swarmed inside, wet and excited. And when the students came upon Scott and Swift, they grabbed the phones from their hands. “Who were you talking to?” demanded a student confronting Scott.

“Ayatollah Khomeini,” he replied. “He told me to tell you all to leave here and let us go.” The Iranian struck Scott across the face.

By 2:00 pm the assault was over. Ode was roughly led back to the embassy compound through the rain. Scott was led out of the chancery, a tight muslin blindfold covering his eyes and nose. Together with the other 61 Americans captured at the embassy that morning, the charge d’affairs and his two aides held at the Foreign Ministry across town, and six other Americans hiding in the Canadian and Swedish embassies, their hostage crisis had begun. A 444-day ordeal defined by isolation and mistreatment lay ahead for most of the hostage. A nightmare of torture and abuse lay ahead for an unfortunate few. [3]

But this is not how the Iran hostage crisis began for most Americans. As the students broke into the embassy buildings, and as the hostages were blindfolded and paraded across the grounds, camera viewfinders focused on them. Photojournalists covering the demonstration, or alerted to the seizure of the embassy, rushed to the scene, snapping off iconic images of William Belk, a towering communications and records officer, blindfolded in front of a small group of marine and diplomat hostages. Film crews recorded footage of Jerry Meile, a communications officer hiding in the interior vault, led blindfolded from the chancery between grim-faced militants. For most Americans the hostage crisis began 11.5 hours after the surrender of the chancery when CBS’s Bob Schieffer, NBC’s Jessica Savitch and Dick Schaap, and ABC’s Sam Donaldson began another 444-day ordeal – an ordeal defined by images of angry Iranian demonstrators, a scowling ayatollah, a powerless president, and the ordinary faces of Americans held hostage half a world away. [4]

Shooting the Ayatollah characterizes Iran and hostage crisis media coverage by quantifying the volume, type, and tone of images and visual techniques used by the American mass-market newsweeklies – Newsweek, Time, and U.S.News and World Report – and by comparing news magazine coverage of the hostage crisis with that of the regular network nightly news broadcasts. By focusing on these orthodox media outlets, this analysis intends to show that Iran and the hostage crisis consumed the attention of the media – and the media’s myriad audiences – at the expense of other newsworthy events and trends. This study will remove the metaphorical blindfold that, once covering the eyes of Americans obsessed with the drama playing out in an embassy under siege, has since transferred to historians obsessed with finding meaning in the way that drama was told. [5]

This study employs content analysis to describe the entire lifecycle of hostage crisis media – from its creation in Tehran and east coast newsrooms, through public communication on the pages of the newsweeklies, consumption by various strata of society, and in comparison with foreign media. Shooting the Ayatollah tests a number of core assumptions about the hostage crisis’ media coverage that dominated the contemporary press and lingers in the current historiography: first, that the media’s lack of foreign reporters denied the press access to Iranian culture and cultural assets [6]; second, that Iran’s absence from the printed and broadcast media prior to the beginning of the hostage crisis left the public and policymakers unprepared for crisis-era antagonism [7]; third, that the crisis was a human-interest story, not a diplomatic or political narrative, and that Islam and the Middle East’s treatment in the crisis-era press was monolithic and negative [8]; fourth; that Carter-era foreign policy decision-makers were immune to the pressures associated with public perception [9]; and fifth, that the Arab world’s view of the crisis was sympathetic to the Iranian revolution. [10] A scientific approach to the crisis-era press demonstrates the fallacy of these assumptions and provides a new, more accurate image of the crisis.

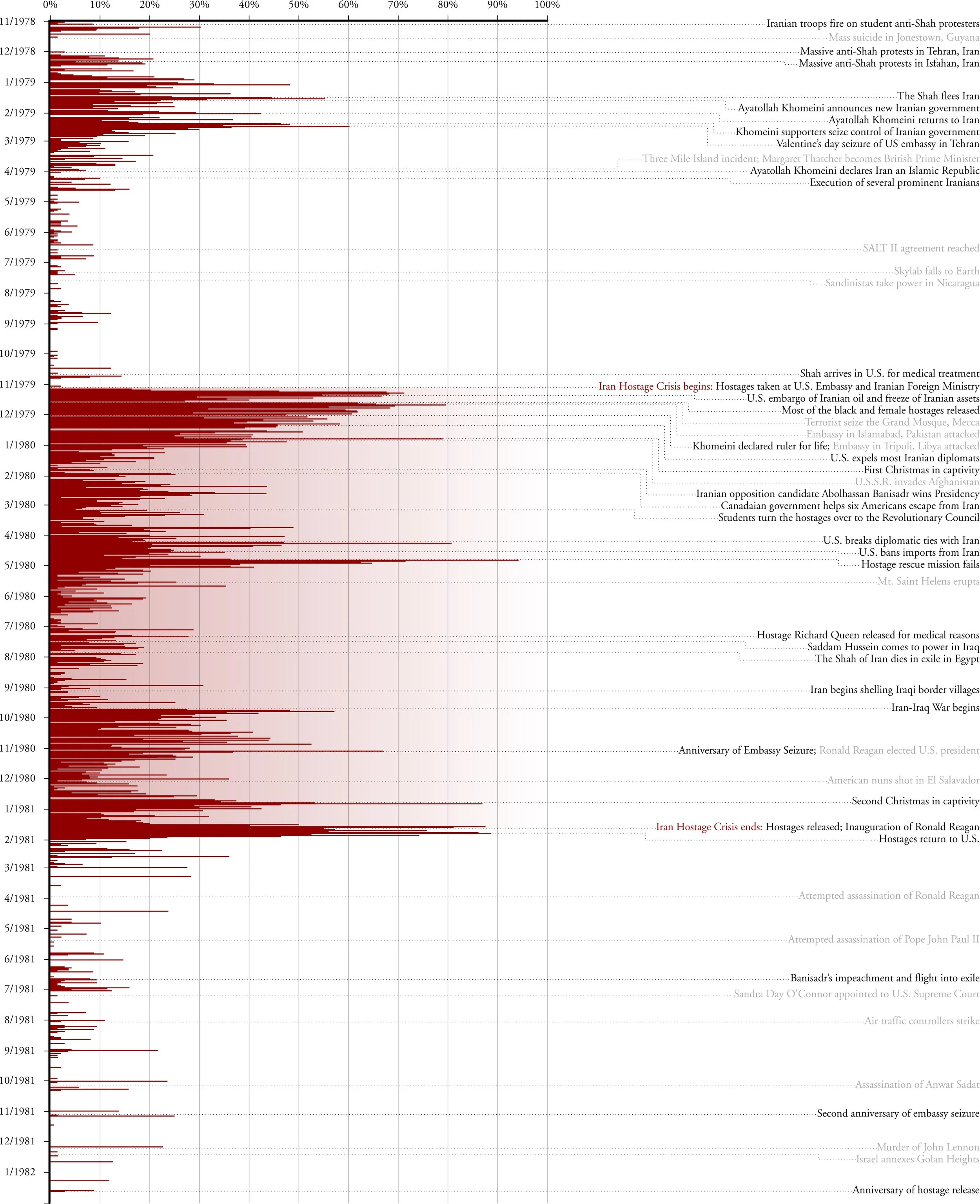

Figure 1.2 — Iran and hostage crisis newsweekly covers during the Iran Hostage Crisis.

That the Iran hostage crisis dominated the contemporary media is demonstrated by a cursory examination of news magazine covers during the 444-day hostage crisis. Over a period of 65 weeks, Iran and the hostage crisis dominated the covers of Newsweek, Time, and U.S.News and World Report thirteen, eleven, and four times, respectively (figure 1.2), and additionally appeared across the top of Newsweek’s covers twice, in the corner of Time’s covers eleven times, and in a secondary position on U.S.News and World Report’s covers seven times. [11] Iran and the hostage crisis appeared on the cover of these newsweeklies more than almost any other issue; the contentious 1980 presidential campaign garnered eleven, nine, and twelve respective covers while the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan warranted only two appearances on Newsweek and Time’s covers and only one appearance on the cover of U.S.News and World Report.

The media is the essence of the Iran hostage crisis – through their use of the American press, the hostage takers and their supportive regime sought to change the mind of the American public about what the U.S. government should do and, thusly, affect change in ways negotiations never could. [12] Their goal was to bypass diplomatic channels and participate as a political force in the U.S. electorate. And as diplomatic channels increasingly broke down, the media became all the more important as a vehicle for international communication. But the crisis is also relevant because the media saw it as the most important story of the time and the president saw it as the most important item on his agenda. It was, according to a White House aide, “the central, dominant feature of the Carter administration from the day [the seizure] happened [until] the day that Jimmy Carter quit being president. It was the one thing that drove everything else in the White House.” [13]

Chapter two, “Revolution and Crisis Through the Viewfinder” argues that magazines are comparable to television in terms of their cultural and agenda-setting influence and that photojournalism is an important and unique lens through which news is transmitted and the first impressions of history are formed. This chapter also shows that, despite editorial differences, visual coverage of Iran was greatly equalized through collective reliance on the two major American news services, the Associated Press and United Press International. It further shows that Iranian photographers supplied a significant portion of pre-crisis and crisis-era photographs, a challenge to the current historiography’s assumption that the U.S. media lacked access to Iran and its cultural assets.

Chapter three, “Pornography of Grief, Pornography of Politics” demonstrates trends in the newsweeklies’ coverage of the crisis, including Iran’s dominance of the printed and broadcast media for a year prior to the embassy siege, a finding that suggests the American public should have been familiar with Iran before the capture of American hostages in November 1979. This chapter also characterizes the visual nature of the coverage, arguing that despite distortions of Iranian realities, there was no monolithic negative image of Islam in the U.S. press during the crisis as often depicted in Orientalist literature. It also shows that a diplomatic, political narrative kept pace with the human drama throughout the crisis and that Iran’s sudden departure from the national press was not because of neglect, but the result of changing public interests and the media’s expulsion by the ayatollah.

Chapter four, “Polls, Public, and Presidents” examines the impact crisis-era coverage had on American perceptions of Iran and Islam. This chapter also explores newsweekly readership, analyzing detailed marketing data and finding that magazines were disproportionately read by a demographic matching the classic description of the foreign policy public. Additionally, the combination of crisis coverage and the administration’s failures to manage the story combined to adversely effect crisis-related foreign policy decision making.

Chapter five, “The Iran Hostage Crisis in the Arab Press” compares American press coverage with that of two Arab dailies – Egypt’s Al-Ahram (الأهرام), one of the most widely read and circulated newspapers in the Arab world, and Algeria’s El Moudjahid (١لمجاهد). This chapter will show that the Arab press, while critical of the U.S., demonstrated no sympathy for the Iranian revolutionary cause. It will also show that American news services and conflicting local foci shaped Arab reporting of the crisis, creating an aggregate coverage that differed from its American counterpart little in substance but greatly in emphasis.

This study takes as its most basic assumption that cultural products – films, television, novels, magazines, news broadcasts, music, etc. – possess value as primary documents for revealing the past. Such products have often been employed to tease out the perceptions of a consuming audience or, more often, to loosely illustrate a point of cultural import in an otherwise disinterested study. But in this analysis, cultural products are measured to determine their outward characteristics and the conditions of their creation. This study will therefore show that mass communications are as much the product of the culture under examination as they are the manipulators of it. [14]

In order to discern an accurate picture of crisis-era media coverage, this essay uses an adapted form of content analysis, a common tool of intelligence and marketing analysis. Content analysis is the systematic and replicable examination of communications – verbal, textual, visual – using quantifiable methods and statistics to describe content, infer meaning, and assess a cultural product’s context both in terms of its consumption and its production. [15] Additionally, this study uses a consecutive sampling method, not a random or proportional sampling technique that might miss significant fluctuations in coverage types and intensity. This is a unique aspect of this study, done both to create a complete picture of media coverage and to avoid criticism and estimations associated with proportions, errors, and standard deviations inherent in non-consecutive sampling. [16]

Content analysis, as employed in this study, assumes that editorial space in printed or broadcast media is not an infinite resource and that “the news-reporting process” must be seen as a “forced choice in a closed system.” Within this system, as something new is introduced, be it advertising or information, something else must necessarily be displaced. [17] This measuring process is akin to scientific observation, allowing researchers to interrogate a large or varied volume of cultural products or documentary evidence in much the same way as a social scientist might interrogate a human subject. [18] In this context, magazines represent a useful medium for study because of their quantifiability and ease of access. But they also represent a good comparative medium for the broadcast media – more often the subject of communications study in regard to the Iran hostage crisis – because both media outlets represent closed-systems of content and have comparable audiences.

This analysis is also based upon the assumption that societies and audiences, like individuals, have only limited attention spans – as new problems and issues are introduced to the public dialogue, existing concerns are retired. This is not a deliberate process. Reporters and editors are often more concerned with getting magazines out on time than with issue displacement or forming public perception. [19] But by looking at the most empirical representations of the media’s forced choice – page counts, advertising space, columns, broadcast minutes – it is possible to discern trends in cultural products just as readily as trends in social focus and changing values.

Such a study is not entirely without precedent. Douglas Little’s American Orientalism demonstrated American perceptions of the Middle East as shaped by National Geographic photography – specifically the visual transformation of the region from a backward, barbarous desert into the modern, progressive oasis through the actions of the brave and industrious Israelis. [20] Melani McAllister’s Epic Encounters also analyzed cultural products – television, literature, and film – that shaped American views of the Middle East. [21] But the need for new approaches to cultural and media history is made apparent by even these studies. The cultural historian’s use of imagination and inference to develop theses, in lieu of quantifiable metrics and quotable policy documents, is frequently attacked. Quantification, a longue dureé perspective, and a more documentary review of the creation and consumption of cultural products can shore up the foundation upon which cultural history is built. Robert Darnton called for the creation of a history of communication in his 2000 American Historical Association Presidential Address and, indeed, such a history would help buttress many cultural studies. [22] This paper is an attempt to demonstrate one such method of analyzing historical communications to create a sophisticated and accurate image of cultural products and their impact.

Indeed, the only significant attempts to quantify media coverage of terrorism are Richard Schaffert’s Media Coverage and Political Terrorists: A Quantitative Analysis and Brigette L. Nacos’ Terrorism and the Media: From the Iran hostage crisis to the World Trade Center Bombing. Schaffert makes no cultural claims about the quality or nature of the coverage – rather, he attempts to connect incidences of casualty and mortality in terror attacks to public anger. [23] Nacos, on the other hand, makes excellent use of social and cultural data, connecting the crisis and a handful of other terrorist events to public opinion and presidential approval. But her scope of analysis is limited to the early months of the crisis, missing an opportunity to measure changing public attitudes and presidential fortunes against the duration of the crisis. [24] Journalism and popular history texts on the subject of the media and terrorism likewise deal very little with pre-September 11 incidents and, when they do, treat situations such as the Iran hostage crisis only as historical background, regurgitating the conventional historiography and offering little analysis. [25] Thus, Shooting the Ayatollah fills a quantitative gap in the cultural and media history of the Iran Hostage Crisis and corrects inaccuracies in the prevailing historiography, buttressing future media and cultural analyses.

Chapter 2: Creation

Revolution and crisis through the viewfinder.

“So let us today drudge on about our inescapably impossible task of providing every week a first rough draft of history that will never really be completed about a world we can never really understand.”

– Philip L. Graham, Newsweek chairman [1]

In March, 1979, Abbas found himself staring through a viewfinder at the bodies of four Iranian generals rolled out of their freezers and on display in a Tehran morgue (figure 2.1). A photographer with the Paris-based Gamma-Liaison agency, Abbas had rushed to his native Iran in September 1978 to cover the aftermath of the “Black Friday” massacre of anti-Shah demonstrators by government troops. [3] Then, too, he had focused his lenses on bodies, secretly photographing bullet-riddled civilians laid out atop the graves of Behesht Zahra. [4]

Unlike most photojournalists covering the growing chaos in Iran, Abbas threw himself into the revolution, a choice that placed him in a unique position to document the movement from within even while threatening to muddy his journalistic objectivity. “My Iranian friends urged me on,” he wrote of his choice between activism and discernment. First, they argued, “we had to get rid of the Shah and then ‘we’d see’. I preferred to risk weakening the image of the revolution, which at that point was peaceful and enjoyed support the world over, than to hide its excesses.”

Figure 2.1 — Four generals in the Tehran morgue. [2]

But Abbas’ revolution was not the revolution of the Ayatollah Khomeini and the mullahs. His revolution, like that of millions of his countrymen, was a progressive cause, linked inextricably to secularism and liberalism. In a single frame shot in a Tehran morgue, Abbas’ enthusiasm was spent. “How could I forget the dignified face of the captive General who was interrogated in front of the television cameras? Five days later, I photographed his body, one of four lying in the morgue. Their trial had been held in secret … this revolution would no longer be mine.” [5]

This chapter explores Abbas’ photograph and the creation of the Iran hostage crisis as a cultural product, exploring what can be learned through a forensic analysis of the larger visual corpus of which Abbas’ image was a part: a pantheon of photography that brought the Iranian revolution and the Iran hostage crisis into American homes on the pages the most widely read newsweeklies of the era, Newsweek, Time, and U.S.News and World Report. After establishing the historical value of news magazines and photojournalism, this chapter uses photographic evidence to explore the creation of crisis-era media and demonstrates that, despite historical and editorial differences, the three major American newsweeklies drew their visual content from identical sources. This chapter also shows that, among individually credited photographers, Iranian photojournalists contributed significantly to Iran and hostage crisis coverage, challenging the established contention that American media during the crisis was universally alien to Tehran.

Witness to history: The cultural value of newsweeklies and photojournalism.

The majority of modern cultural studies, especially those regarding news coverage in the modern epoch, focus on the role of television. This essay, with its focus on news magazines, assumes the equality, and even superiority, of print to broadcast journalism in shaping public perception and influencing foreign policy decision-making during the Iran hostage crisis.

1970-80s news magazines were closer in substance and editorial direction to television than to newspapers. Both television and news magazines aimed to inform and summarize myriad complex issues of national and international import in a compact format, vividly illustrated with striking color images, for people too busy to read more extensive reporting in the handful of national and international newspapers. [6] But where television news tended to focus on a handful of regular newsbeats – such as the golden triangle in Washington – the print press tended to cut across many and more varied newsbeats. [7] And although magazine and newspaper articles regularly carried Washington datelines, they frequently covered developments from many other beats in the capital as well. [8]

These magazines were also more flexible than television in terms of their story selection and the total amount of non-advertising, news content published in each issue – the newswhole. Between November of 1978 and January 1982, the average ABC World News Tonight broadcast had only 21:50 minutes of news content alongside 6:10 minutes of advertising while Time had an average of 50 newswhole pages alongside 52 advertising pages per issue. [9] Time suffered from a higher percentage of advertising content, but its newswhole was significantly larger; the typical television news transcript would occupy less than two columns on the New York Times front page – less than two pages in the typical newsweekly. [10] Likewise, television news was limited to a half-hour format with only 22 minutes set aside for substantive news content. News magazines varied their length to suit editorial needs. During the hostage crisis era, Time ranged between 28 and 63 pages of newswhole, riding the ebb and flow of breaking stories and regular news as needs required. And while practical advertising and printing limitations restricted the newsweeklies at the extremes, this flexibility allowed for the inclusion of a wider variety of stories and more editorial depth than even a week of television news coverage could accommodate, including approximately ten-times the international news information carried by the television news. [11]

That said, the practical limitations of space and time inherent in both the print and broadcast press inspired fierce competition among writers and editors, playing an important role in editing and filtering news essential to domestic and foreign policy processes. [12] The press did not set the national agenda but because it “edits out so much while including so much” it did decide what items were most important once that agenda was set. [13] From the media consumer’s perspective, news that goes unreported, however important, might as well have never happened. [14] Thus the power of the news media is not that it told people what to think but what to think about. [15]

Newsweekly manipulation of cover story content is a good example of this agenda-setting influence. Breaking news or ongoing national and international stories typically dominated news magazine covers. Often chosen on the basis of public familiarity or interest – real or perceived – cover story selections legitimized their subjects, working them into the national dialogue. An ironic aspect of this phenomenon was the refusal by some news magazine editors to include certain divisive domestic figures on their covers, because of the perceived credibility it would assign them, while contemporaneously featuring controversial foreign figures such as Ayatollah Khomeini or Polish labor leader Lech Walesa. [16]

Crisis-era newsweeklies’ were also unique in their use of photography. These news magazines typically devoted one third of their newswhole to dramatic images that buttressed or dominated written reportage. [17] 22% of Iran and hostage crisis newswhole area was so utilized. This emphasis on visual reportage represents a characteristic of 20th century culture that some observers have called the pictorial turn – the realization the rhetorical value of image-dominant media surpassed word-dominant media in every cultural spectrum. [18] Visual reportage became a unique and significant contributor to culture, serving both as a “witness to history” and giving “testimony in the court of public opinion” and may be the only credible source of reasonably true images about world culture and history for later decades. [19]

This emphasis on the visual is no coincidence. Just as television lead stories and print media front pages or cover stories were much more likely to be read than those otherwise buried in news broadcasts or publications, so too were pictures much more likely to be noticed and better remembered than words alone. Research has indicated that people better remember what they see than what they read or are exposed to in other ways. Even in instances of conflicting messages between word- and image-based communications, information gleaned visually is better recalled. [20] Studies analyzing the use of imagery during the first Gulf War, for instance, found that while written reportage was at its most intense and critical, visual rhetoric in leading newspapers echoed the administration’s position, casting administration leaders in positive, if not heroic, lights, and more significantly affected public perception of the conflict. [21] This study’s content analysis is in part based on this premise: that visualizations – in this case, documentary photography – can capture and communicate complex messages either independently or supplementary to text. [22]

The rise of photojournalism in the American print media, fully embraced in most American markets by the 1930s, paralleled the rise of long journalism, the analytical and interpretive coverage of the news as opposed to a basic recounting of newsworthy events. It has been argued that the use of photography to supplement text facilitated the development of this more mature form of journalism, relieving the writer from describing factual events easily captured and evidenced with photography. [23] But photojournalism as a profession and as a unique form of reportage, often independent of text, only emerged later through war.

British Crimean war photography and Mathew Brady’s sometimes misleading Civil War photography first brought dramatic images of conflict to the reading public. The large number of civilian and uniformed camera operators in World War I combined with the subsequent introduction and success of picture magazines and newsreels made photography an integral and expected part of the news. World War II saw an explosion of conflict photography on all fronts, with German photographers documenting the Nazi invasion of Poland, allied cameramen landing at D-Day, and hundreds of Russian photographers dying on the frontlines of Moscow and Stalingrad. Joe Rosenthal’s “Old Glory Goes Up on Mt. Suribachi, Iwo Jima” – considered one of the greatest news photographs of all time – offers testimony to the quality and frequency of war photographers in the field. [24] By the end of the war thousands of military-trained photographers flooded the domestic market. Thus photography accompanied the postwar economic and advertising boom: national associations were formed, elite photo agencies were founded, and photography found its way into nearly every national newspaper and magazine, driving the circulation figures of picture magazines to historic heights. [25]

Photography enjoyed a lauded position in journalism – one of assumed objectivity assigned through the mechanical presentation of reality. This evidentiary quality of photography boosted the value of all print reporting as photojournalism flourished in the 1960s with the invention of the 35mm camera and advances in photographic printing and electronic transmittal. [26] Even as picture magazines such as Life were in decline by the start of the Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis, the advent of color photography in printed news magazines increased the rhetorical impact of images in the press. The newsweeklies had long used color for advertising but it was only after Newsweek published a special color-picture Christmas issue in 1976 that all three news magazines added color photography to their regular news repertoire.Previously considered an editor’s toy by many journalists, color photos quickly came to be seen as necessary additions to the weekly medium, providing an added measure of competition between the newsweeklies, competing directly with television’s visual reportage, already in color, and boosting the rhetorical and marketing impact of certain stories. [27]

The advent of color also changed the way news magazines processed news. Photo editors, often veterans of picture magazines and visual publications such as Sports Illustrated and National Geographic, considered still pictures as important as text, judging photographs by much the same criteria television journalists judged film. At the most basic level, editors and publishers valued photography for its immediacy and impact: “you lead with a strong picture to catch the reader; the stronger or more unusual, the better.” As photojournalism evolved and color became more common photo selection became even more important for weak stories and for photographs that served as stand-alone stories.[28]

That color photography increased in importance relative to written content for the three leading newsweeklies is demonstrated by an analysis of the change color ushered into their editorial processes. In the late 1970s, weekly news magazines were typically assembled over a five-day period – Tuesday through Saturday for Newsweek, Monday through Friday for Time. Editorial processes thinned a wide field of story suggestions based on their newsworthiness, the availability of sources, the timing of world events, or the quality of the reportage. Before the introduction of color photographs to the newswhole, photo selection was rarely thought of as part of the story selection process and rarely considered before the fourth or fifth day of the news-cycle. But after the introduction of color photography, and as a result of changed practical considerations and color photography’s additional visual impact and rhetorical value, photo selection moved up in the editorial process. Editors had to be picky, assigning the most important stories to the handful of color pages in each issue – produced as forms or signatures in multiples of four or eight pages – and balancing the use of color pages early in the magazine with the additional use of color pages at the end. [29] Additionally, in the late 1970s, color pages still went to press at least a day before black and white pages, requiring earlier editorial decisions and more rapid story composition. [30] These factors all combined to push photography forward in the editorial process and eventually add photographic concerns to the initial measure of a story’s worth.

Public consumption of the news media before and during the Iran hostage crisis was affected by photography and the increasing frequency with which dramatic color imagery was used to communicate the news. In the 20th century, the American public became experienced participants in the press’s mediated reality wherein photographic coverage occupied an increasingly central position in explaining the world.[31] The public assumed photographic objectivity, a result of the photograph’s historical role as a supplement to written text and the neutral, mechanical eye of the camera. [32]

This should not imply that photographs have or ever had universal meanings. Indeed, the differences in perception and the frequent disconnect between a photographer’s intended message and the interpretation of various individuals and audiences is part of the cultural worth of photography as a subject of study. Take for instance the photograph of a Chinese student standing before a tank during the Tiananmen Square incident: in the West this iconic image stands for individual courage and popular resistance to an illiberal regime. In China, the image, when shown at all, exemplifies military restraint. [33] This divergence of meanings is further heightened in photography of conflict, where significance and symbolism often become vehicles for national mythologies or patriotic expressions. [34] Images of political terrorism are especially important in their effect on public perception, an affect that in a democratic society with a plurality-based political system is all the more significant.

News magazines, like television news and other print media, affect the national agenda, dismissing some stories while emphasizing others. But unlike television, newsweeklies are flexible, expanding or contracting their newswhole to better accommodate changing coverage demands while preserving their compact format. Likewise, revolutions in photography, from its inception as a supplement to text through its post-war diffusion and the introduction of color in the newsweeklies, changed the editorial process of making news and increased its impact on the newsweekly audiences. Thus magazines and photography are seen as valuable cultural products, easily competing for attention with television. Indeed, the twentieth century belongs to photojournalists – no other epoch in human history has been visualized in such an unduplicated and presumably neutral way, photographs representing “the ultimate anthropological and historical documents of our time.” [35]

Different editors, same sources: The newsweeklies and the wire services.

The three leading American newsweeklies, Newsweek, Time, and U.S.News and World Report have very different histories, editorial emphases, and photographic traditions. Yet, as the news magazines addressed Iran and the hostage crisis, they showed remarkable synchronicity of subjects and sources. Some of this similarity in coverage is the result of the Iranian newsbeat. But in particular regard to the photographic crisis, this similarity can be assigned to the reliance of all three magazines upon the major American news services, the Associated Press and United Press International.

Time, the oldest of the newsweeklies, was by 1979 the most widely read and criticized news magazine in America. Henry Luce and Briton Hadden founded the magazine in 1923, inventing a modern means of news transmission that was less interested “in how much it included between its covers – but how much it got off its pages into the minds of its readers.” [36] Time’s group journalism, a development of the 1940s, transformed news articles from the product of an individual correspondent to a product of multiple correspondents, editors, and researchers. While this practice diminished – largely as a result of outside criticism and internal demands for individual credit – by 1981 it was still intact enough to warrant the condemnation that Time writers and editors often never left their offices in New York to work on their stories. [37] But group journalism allowed Time to develop a very flexible and reactionary style, one in which field correspondents, many of them foreign, would submit material to in-house writers whose output could be tailored by editors without any prepress delays. This style could lead to misinformation and lawsuits, such as Ariel Sharon’s suit regarding Time’s coverage of the Sadra and Shatila massacre in 1984 wherein field correspondents reported from Israel and Lebanon but all published writing and editing took place in Time’s relatively cloistered New York offices. [38]

Such criticisms parallel those often leveled at the broadcast news: that immediacy denies time for reflection and distance from the subject, exaggerating the superficial components of events. The result is news that is ever more processed, ever more authoritative, and ever more detached. [39] Time was also criticized for smothering its readers with raw facts. Critics argued that readers were attracted to the magazine by its “apparent breadth (if not depth) of knowledge” and that, while the magazine does not falsify facts, it uses so many that readers interpret every word in the publication as canon. [40] And though Time has never endorsed a candidate, it has been criticized, as have Newsweek and U.S.News and World Report, for attempting to shape campaign politics though its choice of cover stories, biased reporting, and timing. [41]

Time was, and in many respects still is, known for its unique literary style – timestyle – characterized by descriptive epithets, inverted sentences, alliteration, and the absence of simple descriptive verbs. [42] But the look of the magazine – Time’s departments, typography, slogan, logo, and the signature red bar around the cover – have remained largely unchanged since its inception. [43] Articles remain short, reflecting Luce’s 400-word goal and the magazine’s annual “Man of the Year” feature remains popular, chosen by the editors according to the working definition of “a man or woman who dominated the news that year and left an indelible mark – for good or for ill.” [44]

Newsweek, Time’s closest competitor in terms of audience size, official circulation, and format, emerged in the thick of the Great Depression. Throughout the magazine’s history, its competition with Time has been fierce, peaking in the 1960s when Newsweek temporarily surpassed Time in terms of advertising pages and revenue. In the 1960s, Chris Welles of Esquire wrote of Newsweek, “Over the past few years, Newsweek has often been superior to Time in assessing the meaning, significance and implication of the news …. Newsweek, uncommitted to any formal ideological position, was more receptive to deviations from traditional thinking and as a result usually covered these events with more perception and accuracy.” [45] As far back as World War II, Newsweek enjoyed a reputation for striking black and white photography and was the first news magazine to introduce color photography to its regular reporting. During the 1970s and into 1980 conservative editor Osborn Elliott did not allow his Republican leanings to interfere with his editors and correspondents liberal tendencies, [46] producing balanced and non-ideological reporting. At the time of the Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis critics still warmly received Newsweek, awarding it the 1982 National Magazine Award for General Excellence for “its consistently high-quality reporting and editing, especially of events that require thoroughness and perspective beyond the often meager, surface coverage usually provided to the public.” [47]

The least widely read of the three leading newsweeklies is the Washington-based U.S.News and World Report. This news magazine began as two separate publications, David Lawrence’s 1926 United States Daily, which later became the weekly United States News, and his 1946 World Report. Merged in 1948, U.S.News and World Report has been one of the nation’s top three newsweeklies ever since. Often compared to Time and Newsweek, U.S.News and World Report actually shares very little of their content, focusing on national and international business and government news rather than Newsweek and Time’s wider field of interest including culture, fashion, sports, and the arts. This editorial difference may explain U.S.News and World Report’s success – its focus on forecasting and analysis and its conservative tone foiled Newsweek and Time’s comparatively superficial analysis and liberal leanings. But like Time, the personality and interests of its creator overwhelmingly shaped U.S.News and World Report. Lawrence, a reporter since his youth, one-time friend of Woodrow Wilson, and syndicator of financial news to the Associated Press developed the magazine with a relatively narrow focus on business and policy. [48]

By the late 1950s U.S.News and World Report was larger in size than either Newsweek or Time, though not in circulation or revenue. It consistently exceeded its competitors in political coverage and coverage without editorial commentary. U.S.News and World Report was an early adopter and innovator of many cutting edge reporting processes. It was the first news magazine to experiment with color and computerized prepress and printing technologies. [49] The adoption of these technologies and associated techniques in 1977 helped speed up the magazine’s time to press without the editorial risks inherent in Time’s group journalism process. Nevertheless, U.S.News and World Report remained behind Time and Newsweek in almost every measure – advertising, circulation, audience, and revenue into the crisis-era and beyond. [50]

Thus, by November of 1978, when this survey of the press begins, the three major American newsweeklies were all primed to approach the Iranian situation from different vantage points both ideologically and editorially. But as the Iranian crises demanded attention these differences took a back seat to competitive and content concerns.

Stories, breaking news or otherwise, are often run simply because editors fear their competitors will run them. If Time ran a story on the ongoing hostage crisis, for instance, and Newsweek did not then interested readers would certainly gravitate toward Time. [51] This competition, and the related anxiety plaguing newsweekly editors, appears to have affected Newsweek and Time especially – their content and formats overlapped to a far greater extent than either publication did with U.S.News and World Report. This competition resulted in the most basic equalization of coverage between the newsweeklies. Consider the rapid back-and-forth cover selections of Newsweek and Time in early 1979 (figure 2.2). As the revolution reached its zenith, the shah fled Iran and Khomeini returned in triumph, the two newsweeklies alternated weeks of coverage throughout January, featuring the situation either prominently on the cover or buried inside the magazine, before finally synchronizing in February and carrying simultaneous profiles of the ayatollah and special reports on the Valentine’s day hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy in Tehran. [52]

Figure 2.2 — January and February 1978 Newsweek and Time covers.

But in respect to the situation in Iran, the unique editorial voice of the three newsweeklies appears to have been limited in large part by the availability of sources. Many critics of Iranian revolution and hostage crisis coverage have cited the absence of U.S.-based news bureaus in Iran. This absence is a matter of historical record and not at dispute here. But the closure of U.S.-based news bureaus in the Middle East, and in Iran in particular, was not a regional slight. [53] Rather it was part of a worldwide trend in the late 1970s and early 1980s that saw most international news agencies consolidate their foreign offices. The closure of these embassies was not the result of journalistic negligence but the result of the rising cost of maintaining foreign offices, coupled with increased competitiveness among news services, broadcasters, and publications worldwide. In a world of 4.3 billion people, the expense of maintaining even one correspondent for each 100 million people – 40 international correspondents – was prohibitively high. Of U.S.-based media outlets only the two wire services, the Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI), steadily exceeded this number of foreign correspondents. And of those foreign bureaus that remained in 1979, many were regionally instead of nationally focused. This is especially true in the third world where, except during crisis situations, day-to-day news was of little interest to the American public. Rather than maintain a large number of unneeded American journalists, foreign bureaus supplemented their regional correspondents with nation-specific stringers – freelance journalists and photographers who worked in-country on an as-needed basis and often for more than one Western news outlet.

The alternative practice used by most American news outlets– including the newsweeklies, television news programs and national newspapers – was to have a small number of “firemen,” correspondents “with their bags more or less permanently packed,” ready to fly off to this week’s trouble spot. So while the three news magazines maintained large writing and editing staffs, a large number of domestic correspondents, and a handful of permanent foreign correspondents in the world’s most important Cold War-era capitals, they had no first-hand experience with many of the countries about which they reported. More often than not, American news outlets, broadcast and print, got their international news for these off-beat countries from the wire services. [54]

Mark Twain once said of AP, “There are only two forces that can carry light to all corners of the globe – the sun in the heavens, and the Associated Press down here.” The oldest news agency in the world, AP is a nonprofit corporation founded in 1848 by six New York newspaper publishers inspired by the growth of the mid-nineteenth-century “penny press” and the development of the telegraph. [55] From the outset, AP identified itself as a foreign news service, gathering news from transatlantic liners at its Halifax, Nova Scotia office and wiring it straight to New York for distribution. AP launched its World Service, a dedicated foreign reporting arm, in 1944 after a series of conflicts with United Press and Reuters, and by 1976 it maintained 2,500 reporters in 150 bureaus in 100 countries.. These bureaus were run by American journalists with foreign experience but staffed almost exclusively by natives. Basic news transmission, to which all three newsweeklies and television news outlets subscribed, was frequently supplemented with special reports, audio and video materials, and photography sent across AP’s photowire service. [56]

The newsweeklies also subscribed the AP’s only serious American competitor, UPI. United Press, founded in 1907 as a for-profit company to avoid AP’s cooperative news monopoly, merged with the International News Service of the Hearst newspaper chain in the late 1950s. During World War I, United Press was the first American wire service to offer a dedicated foreign news product. By 1976, it carried 4.5 million words, hundreds of pictures, and special reports across 1.2 million miles of cable and phone line every day from 10,000 full and part-time journalists and technicians in 238 bureaus in 62 countries worldwide. In addition to personalized news and editorials for American consumption, UPI maintained photographic, newsfilm, and audio services for its subscribers. [57]

Figure 2.3 — Associated Press and United Press International photographic contributions by newsweekly.

Indeed, when news breaks from the first world as well as the third, newsweekly editors appear to have responded like generations of newsrooms and news desks before them, asking, “Well, what does the AP say?” [58] An analysis of newsweekly photo credits from crisis-era reporting indicates that all three news magazines relied on the two wire services for a significant percentage of their visual coverage (figure 2.3). Newsweek, with the largest total visual area dedicated to Iran and hostage crisis photography, relied on AP and UPI more than any other content provider, 12% and 9% respectively. U.S.News and World Report, which dedicated the least amount of visual coverage to the situations in Iran, relied on the wire services even more completely, using AP for 33% of its visual coverage, UPI for 18%.

The newsweeklies’ reliance on wire services for their foreign news is not outstanding. In some American newspapers, AP or UPI provide as much as 90% of the international news. [59] Nor should this be interpreted to mean that wire service contributions to the newsweeklies went unfiltered. Just as textual reporting went through rounds of draft revisions as it passed from bureau to bureau on its long trek back to wire service offices in New York and Washington, editors at the receiving publications rewrote the stories to match their own style or worked several subscribed stories into a single larger piece. So too were AP and UPI transmitted photographs filtered by the receiving photo editors. But the newsweeklies’ dependence on the wire services for photography is more significant than its textual counterpart because, while text can be altered to suit a writer’s narrative style, significant limitations – ethical and technological – prevented similar modification of photographic content. Selection or omission, size, crop and position, color or black and white printing were the photo editor’s only editorial options.

The wire services may have had no ideological agenda in selecting which photographs to send out to their subscribers, but news magazine photo editors and designers work as gatekeepers between news service photographers and the reading public. [60] The newsweeklies received many of the same images but, in coordination with competitive and reportage demands, rarely ran the same photos. When such overlaps did occur the newsweeklies often used identical photographs to the reach the same rhetorical ends. As the next chapter shows, this use of identical photography – images of hostage William Belk and the Hermitage Pennsylvania memorial among the notable coincidences – with similar or identical themes equalized crisis-era coverage and limited the conflicting voices of the various newsweekly editorial traditions to create a surprisingly uniform visual narrative. This reliance on AP and UPI for much of their Iran and hostage crisis coverage meant that much of that newsweeklies’ coverage was similar in both tone and appearance.

Through the viewfinder: Photographers of the Iran Hostage Crisis.

There is no monolithic 444-day Iran hostage crisis among photojournalists any more than there is a singular hostage encounter characterized by brutality, torture, mock-executions, and isolation among the hostages. Rather, as former hostage Charles Scott reminds us, “there are fifty-two separate, distinct, and equally valid hostage stories.” [61] If any generalization can be made about the men and women captured in the U.S. Embassy on the morning of November 4, 1979, it is simply that a few of them – a vocal few, well documented in numerous memoirs and accounts of the crisis – were experts in the region, fluent in Farsi, familiar with the country, and sensitive to the ways of its people. The remaining majority of the embassy staff was surprisingly uninformed in the ways of Iran – inarticulate in the local tongues and, by necessity, more familiar with the embassy compound than the revolutionary nation on the other side of its walls.

The same is true of the reporters and photographers who brought the crisis home to the American viewing and reading public. As we have seen, except for an office briefly maintained by The New York Times in the mid 1970s, no major American news outlet maintained a Tehran bureau, relying instead on Pakistani and Indian “stringers,” “firemen” journalists, or their wire service analogues to do occasional reporting. [62] Indeed, the previous historiography, focusing on the broadcast media, holds that during the first days of the hostage crisis, there were approximately 300 reporters in Tehran, none of whom could speak Farsi and few of whom were regionally savvy. [63] And while one must assume that this last comment refers to reporters serving U.S. media outlets, it is surprisingly inaccurate – an inaccuracy demonstrated by even the most cursory examination of crisis-era coverage appearing in Newsweek, Time, and U.S.News and World Report.

Looking at photographic credits appearing in all three magazines before, during, and after the crisis, two trends emerge. First, of those images not credited to one of the news consortiums, AP and UPI, only a small handful of photographers provided a significant portion of the newsweekies’ imagery. [64] Second, and more importantly, many of these photographers were not American. Several photojournalists working for the U.S. press were Farsi-speaking Iranians, citizens and expatriates, and in the case of one particular photographer an active participant in the revolution.

The broadcast press faced the difficult mechanics of deploying camera crews abroad. But all press outlets faced problems of uncooperative governments and alien locales. Such barriers were not insurmountable if the reporter had access to appropriately valuable contacts. But these contacts – valuable and most-often confidential – could not be produced on short notice. Well-qualified foreign correspondents were experienced in the region, knew well how to deal with the government and the public, were fluent in the native language, and were perceptive students of national affairs. As such, local journalists are often valuable resources for international journalists. [65] But in the case of the Iranian crises, Iranian photojournalists were more than just resources for foreign correspondents – they became correspondents. As Abbas would later describe the situation in Tehran, “During the revolution, photography became important in Iran as a form of expression. The hostage crisis furthered the careers of several Iranian photojournalists, since their foreign counterparts found it harder to work in Iran after this.” [66]

Indeed, the top-contributing photographers (figure 2.4) for both Time and Newsweek were Iranian: Kaveh Golestan for Time, brothers Reza and Manoocher Deghati for Newsweek, and Abbas for both magazines. Additionally, a German magazine Stern distributed numerous images taken by the student-terrorists occupying the Tehran embassy. Of the remaining top contributors to all three newsweeklies, four were French photographers: Phillipe Ledru, Oliver Rebbot, Alain DeJean, and Alain Mingam; two were American photographers: David Burnett and Timothy Murphy; and one was Australian: James A. Pozarik. U.S.News and World Report, which featured the smallest amount of photographic coverage of the Iranian situations, employed Reza Deghati as well, but relied much more heavily on wire services and official image outlets, such as the U.S. Navy.

Figure 2.4 — Individual photographic contributions to the news magazines’ Iran and hostage crisis coverage. Iranian photographers highlighted.

This realization reveals a critical, and often marginalized aspect of cultural study. The messages and characterizations of images and other cultural products, so often criticized for stereotypical messages, are not simply functions of their content but also functions of their creation. For instance, previous analyses of crisis-era media criticize the press for 1) their ignorance, linguistic and cultural, in conjunction with their need for immediate results, and 2) their reliance on “experts” whose expertise and bias Said categorizes as typically anti-humanist. [67] The result of these conditions is imagery that projects an unfair image of the Iranians, their religion, and their revolution. But how is this criticism affected by the influence of photographers from among the demonized?

All of these photographers were either on contract for, or employees of, the American newsweeklies and would thus be accountable to the same deadlines and editors. And all photographers, regardless of nationality, faced the same central challenges in creating accurate and marketable visualizations: objectivity and aesthetics. But in the particular case of photographers, the Heisenberg Principle of physics illustrates a problem wherein nationality and language make a difference. [68] How much the photographer affects his or her environment, be it a staid press conference or a tumultuous public demonstration, is highly variable. Does the crowd play to the camera? Can the photographer separate himself from the myopic field of his viewfinder? How well can the photographer navigate the country, its institutions and its personalities?

Figure 2.5 — Hostage Robert Ode, photographed by his captors. [69]

The nationality and loyalties of the photographer can be important. The student-terrorists, for instance, took many photographs of the hostages later distributed by the German magazine Stern. In his captivity diary, Robert Ode painted a clear picture of the impact these photographers had on their subject mater, describing how they released him into an enclosed yard only long enough to get a picture of him of an exercise bike (figure 2.5). Weeks later the student-terrorists tried to coerce him into writing a detailed caption and accompanying statement for the image, encouraging him to send the photograph to Stern himself. [70]

The Muslim Students Following the Imam’s Line were active not only in photography but broadcast media as well, installing cameras and a dish antenna of their own at the embassy compound so that they could broadcast directly to the U.S. networks via cooperating American satellites, bypassing their government’s attempts at censorship. [71] They even provided U.S. television networks with controversial access to the hostages. NBC and the student-terrorists agreed to film and interview a hostage, William Gallegos, selected by the students. The awkward December 10, 1979 interview generated a firestorm of condemnation for the network, from other networks that criticized NBC’s ethics to the administration that disapproved of its exploitation of the hostage. Subsequent efforts to push propaganda videos on American television networks, including Christmas footage of four hostages reading handwritten admissions of espionage and condemnations of the Shah were aired only with an accompanying expert panel or, as in a later and more damning video of quisling Joe Subic, were refused outright. [72]

But a more germane analysis is found by comparing the experiences of professional photographers working in Tehran during the revolution and the hostage crisis: American David Burnett and Iranians Abbas and the brothers Reza and Manoocher Deghati.

Figure 2.6 — David Burnett’s photo of the Ayatollah during exclusive access. [74]

Burnett worked in Iran from January through March 1979 as a contract reporter for Time through Contact Press Images. Staying at the Intercontinental, home to most of the international press, Burnett navigated Tehran with groups of other foreign and Iranian photojournalists, including Time’s Kaveh Golestan. Despite learning quickly to mask his nationality – posing as a Frenchman or Canadian to avoid the attention an American might attract – and cultivating local contacts, Burnett’s access to Iranian demonstrations and the Iranian leadership was often limited. Observing the revolution from without, he could only react to incidences of public demonstration. Likewise, the length Khomeini’s speeches, and the additional time it took for translators to consecutively repeat him in English, often limited Burnett’s access to the imam. [73] But this does not mean that Burnett was unable to otherwise access the revolutionary leadership. In March 1979, after several days of harassing Khomeini’s beleaguered press liaison, Burnett and a colleague were given unprecedented access to the ayatollah. For fifteen minutes, Burnett shot photographs of Khomeini taking refuge from his enthusiastic followers, holding council with his advisors, and enjoying a quiet cup of tea (figure 2.6). This precious access, highly irregular for a foreign journalist, gave Burnett time to shoot 30 exclusive frames of the ayatollah – two of which were printed in Time – and demonstrate that valuable contacts and access could be garnered by a foreign journalist with no prior Iranian resume. [75]

Abbas, the only photographer of any nationality to make a significant contribution to both Newsweek and Time, was an Iranian expatriate living in Paris who became passionately involved in the Iranian revolution after returning to Iran to cover it. Able to navigate both the larger society and the smaller revolutionary movement, his photographs for the Gamma-Liaison agency were taken from a position deeply embedded in the crowd and exceptionally close to the Iranian leadership. Even after Abbas became disillusioned with the revolution he remained in Iran as a self-described “camera non grata.” And while American photographers were forced to leave the country after the government expelled Western reporters, Abbas and other Iranian journalists were able to remain. Staying in Iran for almost two years, from November 1978 through fall 1980, Abbas recorded armed uprisings, demonstrators filling the streets, the changing cast of Iranian leadership, and the seizure of the U.S. Embassy from an envied position among the Tehrani public. [76]

Figure 2.7 — Reza’s iconic photograph of William Belk. [77]

Reza Deghati – an Azerbaijani known professionally simply as “Reza” – was the only photojournalist on the scene when the student-terrorists captured the American embassy on November 4, 1979. While other photographers covered street demonstrations scattered across the Iranian capital, Reza was at the embassy for Newsweek and captured the most iconic image of the news magazines’ hostage crisis coverage (figure 2.7) – William Belk’s emergence from the chancery, bound and blindfolded. Unlike Burnett and Abbas, Reza became a photographer in response the revolution in Iran. As an architecture student at the University of Tehran in 1978, he watched a handful of Iranian troops gun down a group of student demonstrators. By the end of the day he abandoned architecture and took up the camera, shooting alongside European photographers and making a sudden, dramatic splash in the Western press; Reza’s work was first published simultaneously in Paris Match, Stern, and Newsweek. [78]

Manoocher Deghati, Reza’s younger brother, followed much the same path. Returning from film school in Rome to help his brother shoot the revolution, Manoocher soon found himself a target. Manoocher recalls, “A truckload of soldiers rolled by. One of them loaded his rifle and fired at me. The burst of bullets passed on either side of my head. I was alive. I was shocked. But above all, I realized that I was a target because I was taking pictures. That only reinforced my determination.”[79]

No matter how large the media apparatus, the press remained a system of individuals wherein the process of information dissemination remains, effectively, the communication of information from one human being to another. This transmission preserved all the frailties, biases, and ambitions inherent in interpersonal communication. [80] For instance, in the 1990s, approximately 80% of photojournalists were male. One must assume that at least as many of the stringers or contractors in revolutionary Iran were male – indeed, Time’s Catherine LeRoy was among the only female crisis photographers. Thus, the vast majority of images were taken from a male perspective. [81] This is not an accusation of intentional bias. Consider the various steps in the photographic creation-communication process: the viewer looks at a photo in the printed magazine that was organized by editors who obtained the photo from a wire service or photography agency after the photographer or a desk editor had selected the image from part of a larger series shot at the scene. Now consider that the photographer had a far larger scene before him than could be captured on film. Thus the photographer had to be selective about his subject matter – a subject that, in the case of the hostage crisis, may or may not have been staged or otherwise organized. [82] In the photographic and editorial processes – as in the advertising design process – photographers and their editors were often inclined to make decisions about visualizations based on either their own aesthetic or cultural judgments. Such decision-making often produced compelling photographs. But it also produced, with equal or even greater regularity, compositions exhibiting little cross-cultural sensitivity. [83]

Despite different backgrounds and access, and despite objective ambitions, these photographers brought biases to their work. According to Burnett, “the primary reason you’re there is to tell the story, to tell what’s going on … to communicate to other people who aren’t going to be there, who don’t know about it.” But as an American with little Middle Eastern experience Burnett symbolized the American stranger in a strange land; according to American Photographer, “he's been everywhere, but only for an hour.” [84] Notwithstanding the cultivation of local resources, and an ambitious effort to familiarize himself with the revolution and Khomeini’s charged literature, Burnett remained an outsider, conspicuous by his cameras, appearance, and French or English speech. [85] He often learned of demonstrations only after he heard the gunshots and teargas canisters and even relied on demonstrators to help him get the best camera angles in unfamiliar squares. [86]

Abbas and the Deghatis’ participation in Iranian society during the revolution and hostage crisis was tempered by backgrounds and ideologies which placed them in opposition to the aims of the ayatollah. Abbas’ writing reveals a strong affection for secularism and a deep mistrust of fanatical religion – be it Christianity or Islam. Paralleling American writers of the period, Abbas showed frustration with the failure of the secular revolution, and eventually characterized it as devolution, grafting “seventh-century concepts … on to [sic] modern day Iran.” Even as Said criticized Western journalists and photographers for emphasizing the place of martyrdom in the Iranian psyche, and in the ideology of militant Islam, Abbas recognized in his own countrymen this tendency for fanaticism and sacrifice, describing Iran as “the country of the Thousand and One Nights” and as a nation in which “the myth of the martyr had begun.” But Abbas’ perspective – looking out from within the revolution –provides a glimpse of humanity invisible to the non-Farsi speaking journalists in Tehran. His images paint a picture of another hostage crisis, a mirror image of the embassy occupation in which “45 million Iranians [were] hostages to religious fanaticism.” [87]

1970-80s news magazines were comparable to television in terms of their cultural and agenda-setting influence. Likewise, photojournalism had matured by the onset of the Iranian crises, becoming a unique lens through which news was transmitted and the first impressions of history were formed. And despite editorial differences, visual coverage of Iran was greatly equalized through collective reliance on the Associated Press and United Press International for visual reportage. But most importantly, an analysis of newsweekly photo credits reveals that a small number of Iranian photographers supplied a significant portion of crisis-era photographs, a challenge to the current historiography’s assumption that the U.S. media lacked access to Iran and its cultural assets.

Chapter 3: Communication

Pornography of grief, pornography of politics.

How fragile the West is! A mullah proclaims his anathema from a bygone age, taking advantage of his free access to western media, and the West is in turmoil.”

– Abbas, photojournalist [1]

News of the embassy attack traveled quickly. On the morning of November 4, 1979, as students swept over the walls and through the gates of the U.S. embassy in Tehran, reporters and photojournalists covering the demonstration rushed to the scene, writing short bulletins about what was happening on the scene and shooting roll after roll of film of what they saw.

Newspaper, magazine, and wire service correspondents rushed to nearby phones – either on the street, at nearby businesses, or in friendly residences – and called in their bulletins. For Associated Press and United Press International correspondents and stringers, these short paragraphs were called into local bureaus in Israel or Turkey where they were teletyped by cable or microwave to major regional bureaus in Cairo or Beirut, respectively. From Egypt and Lebanon these reports were relayed by cable or bounced off satellites to European offices in France or Belgium and cabled to London before transmission by submarine cable to the AP’s headquarters in New York or UPI’s headquarters in Washington, DC. The entire trip from Tehran to 50 Rockefeller Plaza and 1510 H Street took less than one minute and required almost no human interference.

Once in the United States, World Desk and Word Service editors and reporters took over, editing the bulletins for style and accuracy before transmitting them to subscribers by a computerized system. Within an hour the bulletins were transmitted to subscribers worldwide.

Meanwhile, the photojournalists – independent, contracted, and staff photographers – rushed shot rolls of film and handwritten captions to the Tehran airport. There they met news service couriers or, more likely during the revolution and the early days of the hostage crisis, searched out sympathetic London- or Paris-bound airline passengers and crew. Once the film arrived in England or France and was processed, photo editors used small 8x Lupe magnifiers to sort out the best images from the more than 200 strips of 35mm color and black and white negatives littering their lightboxes. Only the best images were transmitted back to the U.S. Most AP and UPI bureaus and subscribers received these images across slow photo printers. AP’s Laserphoto took as long as half-an-hour to print black and white negatives and individual color composite negatives – four of which, in cyan, magenta, yellow, and black, were required to produce one color photograph. UPI’s Unifax took as long as fifteen minutes to print a photograph, one wet tenth-of-an-inch at a time. A small handful of subscribers received these images across new digital imaging systems such as AP’s electronic darkroom while many international subscribers relied on far slower mail services.

As the story continued to develop, correspondents in Tehran provided further details of the embassy siege and subsequent developments by phone while wire service and news publication bureaus in related countries and diplomatic correspondents in Washington collected relevant supplemental information. This information was gathered in New York or Washington offices and either worked into the main story or compiled to create a separate sidebar story intended to run alongside the main piece. Rarely, frantic telex messages would be sent to photographers in the field, clarifying or seeking new captions for images poised to run in subscriber or contracting publications. Additionally, wire services writers stateside and in local bureaus would draft regional versions of these articles designed to appeal to Middle Eastern subscribers and would field inquires and special requests from domestic and international subscribers as required. [2] The result was the rapid diffusion of foreign news and images to the printed page. Reporters and photojournalists – American, European, and Iranian – revealed to the hungry American news audience an unfolding crisis which journalist George Will once called the “Pornography of grief.” [3]

This chapter quantifies the volume, type, and tone of these visualizations and the techniques used by American mass-market newsweeklies to depict Iran and the hostage crisis for the purpose of characterizing related media coverage. This exercise removes the metaphorical blindfold that, once covering the eyes of Americans obsessed with the drama playing out in an embassy under siege, has since transferred to historians obsessed with finding meaning in the way that drama was told. This chapter shows that pre-hostage crisis coverage was significant and defining, setting the tone for coverage that would follow. It also demonstrates that coverage of the crisis was neither entirely a human-interest story, as it has been most often characterized, nor was it monolithic in its negative treatment of Islam.

Mullahs and mosques: Newsweekly coverage of Iran before the hostage crisis.

The existing historiography argues that, as little attention as Iran afforded in corridors of power, it garnered even less attention in the public consciousness. Despite sustained contact with the United States, “Iran remained terra incognita for almost all Americans.” [4] The U.S.’s closest ally in the Muslim-World, a civilization stretching back over two thousand years, could only elicit a blank stare or a vague Oriental description upon public inquest. Indeed, prior to the hostage crisis, references to Iran were more likely to evoke images of carpets and hookahs instead of mullahs and mosques. As Gary Sick comments, “it is not an exaggeration to say that America approached Iran from a position of almost unrelieved ignorance.” [5]

In this context, it is easy to understand America’s surprise when, on Sunday, November 4, 1979 three thousand demonstrators poured over the walls and through the shattered gates of the U.S. embassy in Tehran. After the embassy seizure, pre-crisis public ignorance was replaced by “the longest-running human interest story in the history of television.” [6] For fourteen months, ABC’s Nightline opened with, and Walter Cronkite’s CBS Evening News closed with, reminders of the hostages and their plight in Iran. News coverage of the hostage crisis garnered at least as much sustained media attention as the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and Watergate – only the 24-hour cable-news network’s coverage of the 1991 Gulf War later surpassed it. [7]

Some academic attention has been paid to U.S. media coverage of Iran before the revolution. A survey of pre-revolutionary newspaper and newsweekly coverage found that the Pahlavi shahs controlled media access to Iranian dissidents as carefully as they limited American intelligence access to them. [8] With little American media presence on the ground, and unable to depend on native stringers who could not be relied upon to write articles that might, if published, result in their arrest, American news outlets were left echoing the voices of U.S. foreign-policy makers rather than pursuing independent information. [9] But Iran was not so closed and veiled a society to prevent journalists –to say nothing of intelligence services – from accurately reporting on the nature of the shah’s regime. Nor is it only hindsight that reveals the fractured society in Iran before the revolution, as the writings of a few reporters and numerous western academics between 1954 and 1978 demonstrate.[10]